F. Mark Modzelewski, Treeline Its an overused phrase, but very true – running a business is a lot like running a race. To burst from the blocks first, avoid wasting energy, picking up the cadence to stay ahead when challenged, these are all elements of the winning formula for the world of business and track and field. Today companies need to run faster than ever. Laggards get disrupted, sprinters do the disrupting. The speed of change borders on oppressive and the only winning strategy is to develop ideas and products and get them into the hands of customers – quickly. Legacy enterprises stumble from the blocks and get dropped in the race to innovate. Over years of operation they have become risk averse, concerned with appearances, weighed down by processes and procedures, and require a whole hierarchy of people to reach agreement in order to pursue any new idea. They are better suited to sponsor an Olympiad than run in one. Design Sprints are a fantastic way for legacy companies to get back in the race of actually innovating.

Author Jake Knapp recently noted that “Speed keeps you authentic. If you’ve got a weird, opinionated, crazy, possibly-stupid-possibly-great plan, and you take a long time to think it through and make it perfect, you water it down and wash out the goodness.”

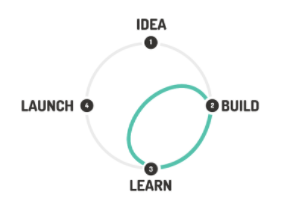

Knapp is the tech industry’s guru on the subject of “sprinting.” He worked at Microsoft, Google, and GV as a designer and he developed a method called the Design Sprint that is gaining traction in companies around the world. Essentially, a Design Sprint takes your organization from an idea to receiving customer feedback in a work week — action-packed but with no overtime. The begins with a group of people huddle together in a room surrounded by white boards charting a path towards their goal and by day five, they are bringing in customers and letting them play around with the prototype they created just the day before. Undertaking a Design Sprint means rapidly mapping out the group’s ideas, finding the epicenter of the problem, sketching user scenarios, making hard decisions and then creating a prototype to share with potential users. The prototype is a mockup, put together to see how a user interacts with it, whether it be a faux app, a sales script, a new benefits program, or an industrial IoT device. It has to look and feel like the real thing even if it doesn’t actually work. There is no engine under the hood because that’s not the point of the Design Sprint. The point is figuring out if you should be building a sedan in the first place, before you spend money and precious R&D time on putting an engine in it. Maybe your audience needs a hatchback? Perhaps a minivan? Or maybe they don’t need a car at all and you’re solving the wrong problem? Do Design Sprints work for every company in every situation? Fair question. The answer is, sort of. Success stories of Design Sprints at Slack, Nest, Blue Bottle Coffee, Platform Science and hundreds of others should convince you. But the Design Sprint is essentially a product development technique. Any such method is only as good as the people and execution behind it. And when it comes to Design Sprints, your organization needs a complete buy-in.

There’s no partial Design Sprint. It’s not a “Design Jog.” If you try to half-ass it, you’re dead in the water. Now, assuming you have the support of senior decision-makers, you need a big problem to solve. In large organizations, those are never in short supply: an entry into a nascent market, the revamp of a stale product, or a massive administrative challenge related to a recent restructuring – take your pick.

It starts by clearing out an entire week on your team’s calendars and get a ‘Decider’. Without an empowered ‘Decider’, decisions won’t stick. Sign off is key. If your Decider can’t join the entire sprint, have her appoint a delegate who can. Once you kick off, avoid distractions and stay on schedule. No phones or laptops. No checking email surreptitiously. It’s like going to a trainer at the gym: it’s amazing what results you get if you just listen. The real magic of Design Sprints reveals itself the fifth and final day when you show the prototype to customers. This is a simple business truth: the faster you can get a “thing” in customer’s hands, the better. They’re the only arbiter of your efforts. Nothing is as valuable to a product team as user feedback. 99 times out of a 100, an average team with good customer insight will create a much better product than a group of rockstar techies building in the dark – because it doesn’t matter how sleek your designs are, how efficient are your API calls, or how stable your releases if what you’ve built is not what customers want. The faster you show users the product, the earlier you get that most important piece of the puzzle. The more rapid your release cycles, the more information you accumulate. This is why speed wins. Knapp’s Design Sprint process is a huge step forward, but it’s not gospel. There is still room for growth and adaptation. We do it all the time at Treeline. We have played with the format, condensing and expanding the timing or adding modules. We included upfront research and brought in designers and experts for the full length of the exercise. We have seen some of the changes work fantastically and others reinforced how brilliant simplicity of the original format is. One area that we continue to experiment with is creating a better system for hardware. The adage that hardware is hard is as simple as it is true. Mocking up hardware in a manner that still allows you truly share a semblance of the real product is tricky and we work with different approaches all the time. From giving the team more than a day to put together something that works, to shooting a commercial of the product, to anything on the scale between hands-on experience and presentation. Typically, this kind of activity is the domain of startups. They’re nimble. They aren’t bogged down with corporate inertia and bureaucratic hassle. But stay with us.

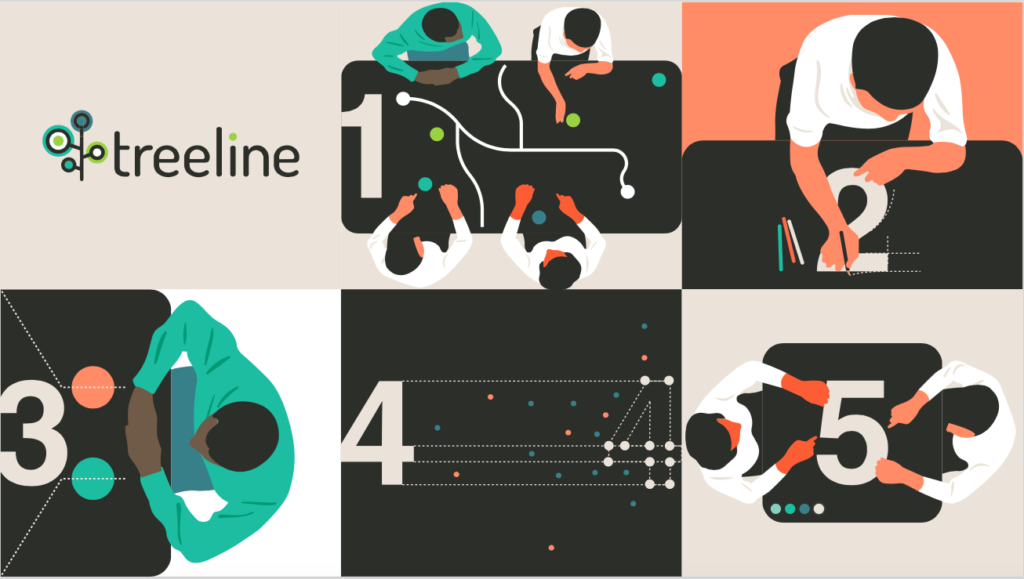

At Treeline, we adapted our own process to incorporate Design Sprints into development of multiple internally designed products, as well as part of two venture-backed startups we have spun out in the past 6 months. After sharing the process with our clients, we have suddenly found ourselves applying it across the board: not just to startups, but to telecoms, a leader in the personal electronics field, and even for government clients.

Large companies and legacy organizations can apply this process just as well as any startup. In fact, in some aspects, incumbents are better positioned to act quicker than much smaller contenders with appetite for disruption. An existing enterprise has all the resources that a startup lacks: cash to spare, industry know-how, a network of partners and an existing customer base. But too often they use these resources to defend their current positions rather than to conquer new ones. The key to success is to let go of the defensive, reactive strategy built on the erroneous premise that your organization can’t be disrupted. Enterprises have the power to shape the market with their products, but to do that they need to unleash the creativity that already exists within their organizations. Act instead of react. Go with your gut and test what it’s telling you. It might sound contrary to the business common sense, but research shows that decisions based on intuition are often more accurate than those made after prolonged analysis. Just remember that the first days of every product always have a giant pile of unknowns, and that the customers are the only ones with actual answers. So force your team to go with their hunches. Make them test a hypothesis against actual users with individual quirks and tastes. You’ll see these quirks morph into habits, patterns and needs. This is how you discover what the customer wants. This is how you run fast. Illustration by Ola Jasionowska

Our firm Treeline is made up of startup founders, hardware hackers and amazing designers and developers. We embraced the Design Sprint because it’s the essence of how we’ve been developing innovative solutions and incubating new startup ideas for over a decade. The structure of the modules, the simplicity, but first and foremost the speed. Design Sprints are free from prolonged deliberation, fussiness in preparation, and endless second- guessing. Even when you pursue an idea that inevitably doesn’t work, it saves vast amounts of resources, money and time. When you fail you just brush yourself off, take the learnings and get ready for the next race.

Our firm Treeline is made up of startup founders, hardware hackers and amazing designers and developers. We embraced the Design Sprint because it’s the essence of how we’ve been developing innovative solutions and incubating new startup ideas for over a decade. The structure of the modules, the simplicity, but first and foremost the speed. Design Sprints are free from prolonged deliberation, fussiness in preparation, and endless second- guessing. Even when you pursue an idea that inevitably doesn’t work, it saves vast amounts of resources, money and time. When you fail you just brush yourself off, take the learnings and get ready for the next race.

Outrunning DisruptionApril 29, 2018