Barry O’reilly teaches us how to rethink strategies by letting go of past habits to achieve stronger and lasting success in the ever-changing world of business

Barry O’reilly teaches us how to rethink strategies by letting go of past habits to achieve stronger and lasting success in the ever-changing world of business

You co-wrote Lean Enterprise, which guides technology leaders on how to bring the most value to their business and founded an innovative entrepreneurial program. Can you tell our readers, in terms of your background, what motivated you to then write Unlearn?

In 2014, I wrote a book called Lean Enterprise, which was really a response to Eric Reese’s The Lean Startup. His book was very popular in the startup community at the time, but larger organizations were trying to understand how those ideas could also be applied to them. They wanted to see how experimentation could look for them, as they were also dealing with innovation—just in different ways and on a different scale.

My background is mainly in leading innovation and transformation initiatives and scaling them up in larger businesses. Along with Jez Humble and Joanne Molesky, my co-authors, we wrote Lean Enterprise to illustrate what the culture of experimentation and learning looks like—not only in product development, but also in finance and HR, as well as with internal processes and the overall way large enterprises are run and organized.

That book was really well received, and lots of companies that try to lead change or transform themselves have adopted it. In writing that book, I also had the opportunity to work with a lot of senior executives and leaders in Fortune 500 companies, and disrupt the scaling of businesses here in San Francisco. While working on that book, I was taking note of how we learn new things and implement them in business. Of course, learning new things and implementing them is hard to do—but it’s possible, and people do it. Through my time spent working with those leaders, I started to realize that the limiting factor to elevating performance wasn’t necessarily in the challenge of learning new things—rather, it was in the inability to unlearn existing behaviors. That idea really resonated with me, so I tried to create a system that would help people constantly adapt their behavior to the changing circumstances that they worked in to try and achieve their objectives.

That got me really excited, working with and coaching senior leaders to build a system based on self-experimenting with different behaviors, new thinking, new methods—all with the goal of increasing performance and getting better results. Unlearn is sort of a retrospective view of going through that process with those senior leaders. It’s a system I think could be applicable not only in business, but also in your personal life and in any challenge you’re trying to tackle.

In coaching these innovation leaders, what have you found to be the biggest obstacles in letting go of old habits and transitioning into new behaviors?

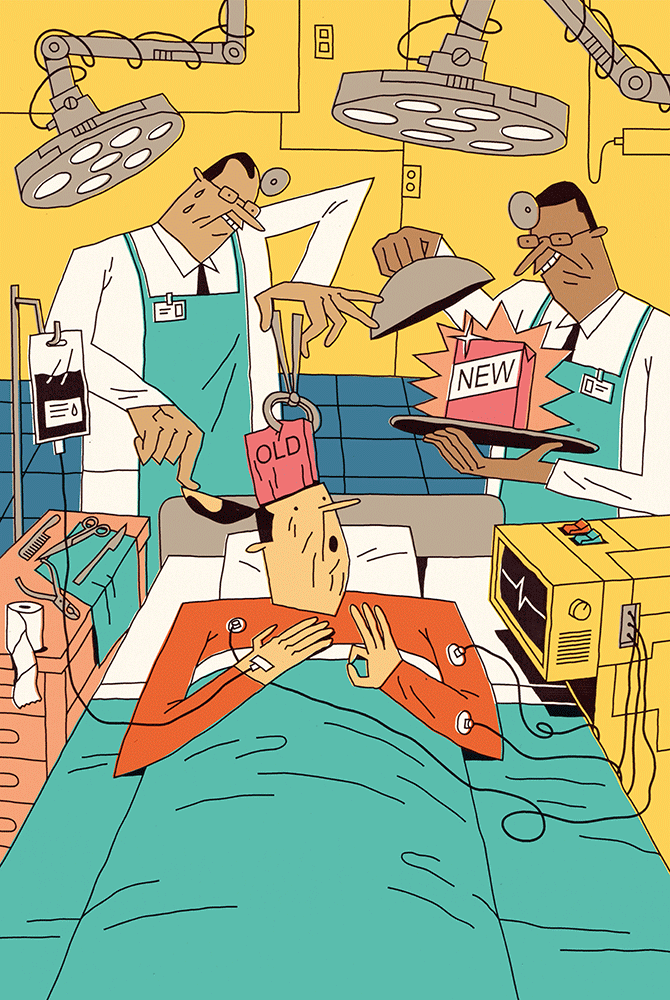

Well, it’s tough for anyone to learn new behaviors. As a senior leader in a company, your past decisions and actions—otherwise known as your behaviors—are what made you successful. In many cases, they’re what turn you into the CEO of these massive companies. So, the feedback mechanisms that are in place are letting you know that you’re doing the right things, you’re making the right calls, and you’re overall reaching success.

What’s often hard for these senior-level executives is recognizing what parts of their behavior are not leading to success, and then knowing when to adapt. A lot of that requires humility—in recognizing that there might be a better way to do things. It also requires courage to recognize that the behaviors you engage in aren’t driving your desired outcomes, and that you might need to adapt rather than place blame or find fault in what other people are doing. Finally, it also requires you being comfortable getting uncomfortable—which involves trying new things that you might not be good at, and experimenting with new behaviors.

That’s difficult for a lot of people. To top it off, a lot of senior leaders don’t like to fail. They’re not used to not being good at things. So, you really have to create a lot of safety to allow people to experiment with failure, learn new behaviors, further experiment with new methods, and to use all that as a way to innovate their own behaviors and hopefully get extraordinary results.

You really have to create a lot of safety to allow people to experiment with failure, learn new behaviors, further experiment with new methods, and to use all that as a way to innovate their own behaviors and hopefully get extraordinary results.

You also have a consulting program for business leaders, called ExecCamp. What led you to start this program? How does it work?

ExecCamp is a mechanism where I get executives to leave their business for up to 8 weeks at a time, with the goal of launching new businesses to disrupt their existing companies. It gives these leaders the opportunity to step out of their existing business and experiment in a safe environment with new techniques, new skills, and new tools to try. This allows them to innovate new potential products or services as a way of not only disrupting their business, but actually disrupting themselves as well. For many, the chance to experiment with new behaviors and new thinking ultimately leads to transforming the businesses they lead—and transforming themselves.

I’ve run that program for companies like International Airlines Group, who are the 6th largest airline in the world, as well as JFK Airport and Telkom in Indonesia. These massive organizations realize they can’t keep doing the same innovation off-sites while expecting to have a different result accompanied by major breakthroughs. They recognize and are courageous enough to take a different path and challenge themselves, get outside of their collective comfort zone, and they reap the rewards as a result of doing that.

What has been the rate of success of your program? Do you have any examples you could use to illustrate its effects?

In the case of International Airlines Group, they created the first ever blockchain identity management system for the airline industry. It’s a transformational idea for understanding people’s movement with better fidelity. We created improved machine learning algorithms to process their customer data—it used to take months, now it takes minutes. IAG also started the airline industry’s first ever venture capital firm, Hangar 51. They made all their airline data and assets available to startups as a way to leverage and build new products and services on top of their existing assets—in ways the airline industry just couldn’t be aware of.

They really shifted the model of how innovation was done in the airline industry. They’ve even launched an entire new airline called Level, a transatlantic low-cost carrier airline operating between Europe and North America. In the first day, they sold 52,000 tickets for flights, and 150,000 within the first month. So, they really innovated the way these big legacy airlines are operating and now they’re much more focused on technology-driven innovation. Ultimately, though, while the products and services are great, it’s the shift in the leadership mindset that’s probably been the biggest impact because now you have these leaders who’ve been through an ExecCamp who could go back into companies and start to coach other people how to do innovation more effectively in their organization. And they’re starting to really reap the benefits of that.

I tried to create a system that would help people constantly adapt their behavior to the changing circumstances that they worked in to try and achieve their objectives.

I’d like to jump back to your book for a minute, and look at it from a broader standpoint. Can the principles discussed in your book be applied to other settings and situations outside of tech companies?

I guess the way I think about it is, if you’re not a technology business, you’re probably already in trouble. If you’re not seeing technology as a strategic capability in your business, you’re probably going to encounter some severe difficulties. But again, technology is only a way of accelerating a lot of manual processes.

Our cycle of unlearning that we’ve created in the book is a system for individuals to adapt their behavior. So, it’s not reliant on technology whatsoever—it’s reliant on you recognizing the methods and tools that you’re using to try and innovate, understanding when they’re working and not working, and identifying where you need to adapt them. In that sense, it’s technology-agnostic. It’s really a personal system to transform your own behavior and thinking. But, you can accelerate that by leveraging technology to gather more data, to have informed, better decision making, to understand how your customers are interacting with your products and services. And to go exponential. That’s really the benefit of technology, but the system is not reliant on technology in any way.

Can you reveal any examples of “experimenting” as you talk about it in your book?

Yeah, with the example of me even trying to write the book, I realized that writing and typing was actually a really an inefficient way for me to create content. It was really slow. It’s hard for me to write, and I’m not very good at typing. So, I started to experiment with different ways of creating content. Working with my writer, we started to do interviews and record and transcribe them.

A 30-minute interview could conjure 10,000 words. So, I would create these mini keynotes and give them for each chapter, and then we would send the recording to the transcription service. They would transcribe the whole thing, send it back to us within a couple of hours. The editor would then edit it into shape and ship it to me early, it was like an MVP for the chapter. Then, we’d work on writing additions and improving it over time. It ended up being a really interesting experimental approach to writing that I used to help me achieve this big aspiration I had, which was to write a book.

Starting small—doing short interviews, recording them, and then transcribing and editing them and making progress towards completing the book—that’s been a lot of fun. We figured out the best method and unlearned what I had initially thought about writing—that writing doesn’t have to mean typing, and that you can create content in lots of different ways.

We figured out the best method and unlearned what I had initially thought about writing—that writing doesn’t have to mean typing, and that you can create content in lots of different ways.

One last question. Can you give us one work or life hack that you use on a daily basis to keep yourself motivated and to achieve success?

I think one of the mantras from the book is to think big and start small. In front of my desk, I’ve got some pretty big aspirational outcomes that I’m aiming towards. Every day, I look at them and I try to think of one small thing I can do that will help to keep me moving towards those larger outcomes. So, I feel like I make a little bit of daily progress towards something very big down the line. Just taking a small step every day makes me feel successful. It helps me to test if the big idea I hope to achieve is real or not with a small experiment, and by constantly making traction to get there. It’s a great system for me to live by. I also used this system to write the book—in fact, I just wrote a blog post titled Unlearning How to Write a Book, where I shared my experiences about the experiments I went through as part of the book writing process. The book was a big outcome that I wanted, but I took small steps every day to complete it.

Barry O’reilly is the founder and CEO of Execcamp, an entrepreneurial experience for executives that seek to reinvent the future. He is also a business advisor, Entrepreneur, Keynote Speaker, and Author of Unlearn and Lean Enterprise.

Keep up with Barry on LinkedIn and Twitter.

Illustration by Krzysztof Nowak.