Most of us have fallen victim to the temptation of fighting too many battles at once. When the world is moving so fast, it might seem like the only way to take advantage of every opportunity is to do everything, while spreading ourselves far too thin on all counts. Let’s just say it: we’ve become greedy in our efforts; we think that diluting ourselves horizontally will bring us results on all vertical levels. This is often a dangerous fallacy, as the story ends in some form of tragedy—either we end up with all our resources completely depleted; we feel torn in a million different directions trying to keep everything afloat; or we end up embodying a “Jack of all trades, master of none” scenario.

Multiple Tasks, Few Results

When it comes to the human mind and its capabilities, the truth is multitasking is not actually a thing. Our brains are incapable of working on two or more tasks at the same time—and studies prove it. We try to multitask—particularly at work—because it makes us feel more productive. Crossing off to-do list items gives us the gratification of work completed, but unless that work is well prioritized and planned, it often doesn’t drive any real progress on our overall mission.

Instead, we get caught in these endless cycles of juggling minor, major, and useless tasks all at once—tirelessly switching our attention and juggling our focus in a knotted string of productivity-chaos. This kind of self-imposed ADHD also takes a toll on our mental capacity. With each ongoing switch, our focus and awareness diminish, exhausting our mental energy. Our efforts to multitask not only result in care-less mistakes, they actually delay completion time and prolong each individual process. In effect, if you try to complete a bunch of cognitive tasks at the same time, you will not only half-ass them and diminish their quality, but, it will also take you longer than if you had approached them sequentially. Some studies show this can result in a loss of 40% of your weekly productivity.

Some of you might be thinking, “yeah this is likely true for the non-digitally native, but surely millennials raised in a world of constant information overflow can multitask with ease?! Hell, that’s why all those startups can unleash so many innovations, right?”

Wrong.

Youth is not immune to the inefficiencies created by multitasking, any more than all humans. Even young brains have short-term memory limits that are the same as those of older adults. A study at Stanford University, led by Clifford Nass demonstrates that multitasking just doesn’t work—even in the case of college students infused with youth, Adderall and gallons of Mountain Dew. They crap out when juggling things. Nass’ study found that when people are asked to deal with multiple streams of information at once, they can’t pay attention, remember, or switch between them as well as they thought they would.

In a world of infinite resources, you would be able to pursue every deal, fix every bug, and complete every project. You would expand your product vertically and horizontally. You would launch more products. But that world doesn’t exist. We live in the world of scarcity and limitations. There’s never enough money, or time, or people to put out all the fires.

So why on earth would you want to spread your already scarce resources even thinner?

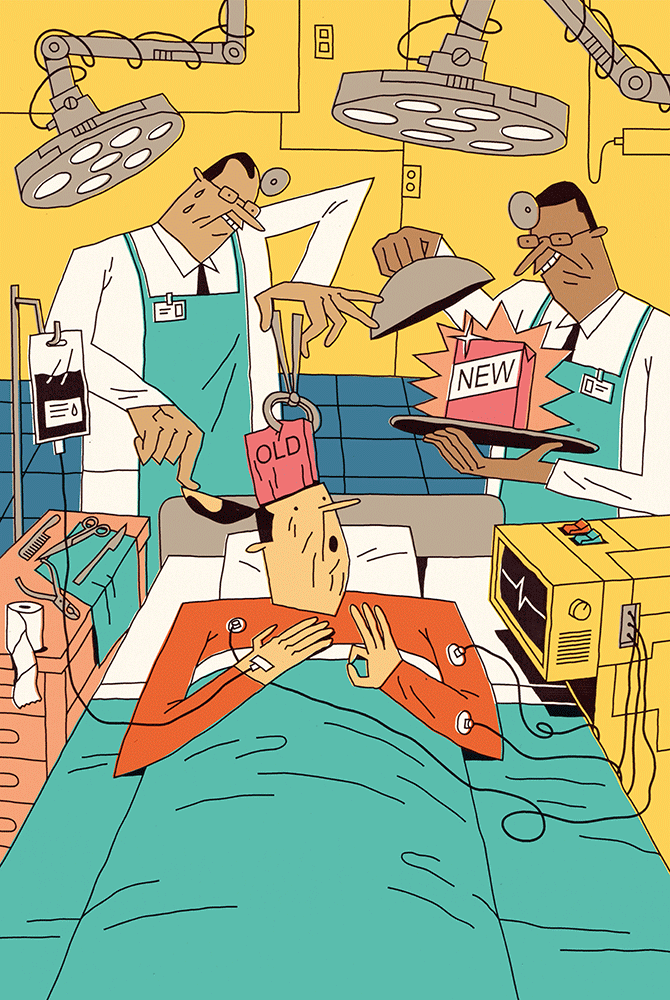

Multitasking: When the “Ultimate” Solution Needs Its Own Solution

Multitasking doesn’t just go wrong when it comes to managing your own tasks in the workplace—it spreads like a virus through tasks, teams and projects as everyone you work with starts adapting the same “juggling game” mindset. At most companies, you probably have a team of five to 50 people tackling a variety of projects and multiple aspects of those projects. Engineers handle QA and build their own tooling. Designers have their hands in everything, from blog illustrations to interface mockups. Customer service reps are responsible for social media. And it’s okay—you’re growing fast, things change all the time and you need to adapt. Flexibility is a good thing. But, there’s only so far you can stretch a rubber band before it snaps—and ultimately, lack of focus due to chaotic, interrupted, and distracted efforts will lead to failure.

There’s a difference between “multitasking” on a micro-level—as a way to adapt to changing needs—and “multitasking” in a heavier sense of the word. Where we really see the harm is when multitasking as a mentality starts being stretched out onto a global scale. It’s one thing to juggle small-scale tasks throughout the day, but if you have one person constantly switching between multiple job roles and responsibilities—that likely will hurt more than it will help, especially in the long run.

Small teams are great at being nimble, but they absolutely suck at managing complexity. To untangle complexity, you need specialization. And if you run multiple projects in a small team, you force people away from specialization and towards being generalists. A team of six developers can fill in the gap if one person is away. Two teams of three are much more vulnerable. Departures, vacations, and sick days will happen. Trivial things will ruin your plans if you specialize too early.

This doesn’t only apply to writing code. Yes, if you try to build two products instead of one, it will most immediately and obviously affect the technical folk. But, as long as your team cannot afford to focus, the ripple effect will spread across the company. Customer service and sales reps now need to know much more in order to operate successfully. Designers need to keep making sure all products are aligned aesthetically. If you decided on two business models, you put a lot on the plate for the admin team. When you make your team multitask, complexity increases exponentially—but the ability to handle it goes out the window. In other words, you take away your team’s greatest strength.

The Solution: One & Done

In an interview with First Round Review, Nate Weiner, the founder and CEO of Pocket, recalled a story. They had a team of 20 and around the same number of projects scheduled for the quarter. Unsurprisingly, their estimates were way off. In trying to multitask, they delivered on just 25% of what they had committed to.

This is a common startup story. With so many opportunities just waiting to be explored, it’s hard to prioritize. But running a business is all about difficult decisions—and this idea of multitasking and its dangers is one of them.

At Pocket, failing at most of their planned projects made them realize they needed more direction. They changed their approach to product development. For each quarter, they took an “all hands on deck” approach for each project, on an individual basis. After some time they picked up the pace and switched to a 30-day cadence. But the principle remained the same—at any given moment, there is only one priority for the company. The goal is clear and everyone is working towards advancing it. Today, Pocket is a beloved product and an indispensable app to anyone who reads a lot online.

In our offices, we apply this “guiding light” technique by breaking things down and getting granular, ensuring each project has a simple problem statement our team is focused on. Every week, every project also has a milestone and deliverable attached to it, called out by the PM and understood by the team as a guiding light and a necessary achievement for the success of the project.

It’s a chit, a record of something you owe. You owe it to yourself and the team to get that task completed—no matter what.

We also employ a secret sauce technique called “One and Done.” At our Monday morning PM meeting after the previous week’s projects and goals are reviewed, and before framing out the meta-targets for the week ahead, we call upon everyone to write out the “one thing” they will absolutely get done that week. Each person’s “one thing” is then put on a sticky note and affixed on the main wall that everyone must pass. It’s initialed so that everyone knows whose goals are whose. And it’s kept in a highly visible place—right where it will be passed as you walk in every morning and out every night. Right there, on the way to the kitchen and the bathroom. And it stays there until it’s done. Because if you fail to hit your target for the week you must re-estimate it, and add a “+” for the number of extra days it will take. Each week gets a new sticky note color so those behind also visually stick out. Excuses for missing the target aren’t taken all that well because while we look at those factors, the whole idea is that you plan for the unplannable and stay on task and on schedule. The lagging sticky note then serves to act as a friendly-but-clear Scarlet Letter, one that again, everyone must pass over and over again, all week long.

We have an odd term for stickies that we got from our team in Krakow, Poland—’karteczka’ (pronounced: kar-TESH-kah). Basically, it’s a chit, a record of something you owe. You owe it to yourself and the team to get that task completed—no matter what. Having this process doesn’t mean it’s the only thing you do all week. It’s not like there aren’t other tasks that are there to be tackled, but what One and Done allows us to do is to say “No.” No—to other requests, people pulling at you, texts, emails, white noise—because you will be held accountable. It gives you the power to draw a line in the sand and say, “No, I can’t take on that other task (or project, or meeting) because we all agreed that this ‘one thing’ is what I need to get done by COB Friday.”

It gives everyone the power to get things done and focus on what matters most.

Illustration by Kinga Offert