Storytelling as a Methodology to Create Blue Sky Technology and Innovation

Rapidly changing political, economic, and employment landscapes are a prevalent and pressing concern for most. How one manages a career or a strategy to properly educate our children for the uncertain future our civilization is enthusiastically forging are constant concerns for many.

Each quarter those many become even more.

Roboticist Hans Moravec created a useful illustration and analogy of the use and application of AI, in which rising water in a landscape of mountains and valleys drowns previously exclusively human tasks. The peaks of human achievement he predicts will last the longest are inhabited by artists, scientists, and authors.

While liberal arts majors may now rejoice this is a terrifying and encroaching reality.

Some luminaries have theorized that the coming technological shifts will enable a new era of human/machine partnership that will free humanity to be creative and do what it does best. Gary Kasparov argues this in his book ‘Deep Thinking’, citing the emergence of more chess Grandmasters from more parts of the world after his loss to Deep Blue, because people are able to learn and play with computers.

However, given that high-powered, lucrative white collar jobs are now being routinely automated away Moravec’s drowning out of jobs is the pressing reality over Kasparov’s chess collaboration.

Also, given the cultural and intellectual containers that guide and shape organizational and individual thinking there are intrinsic barriers to guiding society to a healthy future.

I’ll tie this in at the end, but a good working metaphor is if you’ve ever visited your middle school after you have become an adult note the structure of it. Think how that structure will affect the students just as you were affected compared to the experience of going through middle school yourself.

Culture is like that, too.

Every year at the annual DARPA Robotics Challenge top minds and teams from the world’s illustrious institutions send machines through a competition landscape in which points are awarded to the robot who drives a vehicle and gets out of it, opens a door, drills a hole, screws a valve closed, walks through rubble, and walks up stairs.

The event and technological collaborations and achievements are impressive and passionately done by impressive people. Because of all this impressiveness something quite notable is the nearly monastic chant that the robots and technology developed in the challenge. This will be used to assuage the daily calamity of Fukushima and for disaster relief in general.

This is a fantasy and collective cognitive dissonance on the part of the participants and commentators, as the next thing to be added to the robots will be a gun and the next achievement for that robot will be to vaporize someone’s child in some sundry Muslim nation.

Concomitantly or downstream the tech will vaporize someone’s job in America. For example, the current administration’s crackdown on migrant labor is having the result of increasing the speed at which agriculture jobs are being automated rather than a return of jobs to American citizens.

Given the conservatively estimated $700 billion per year America spends on its military (this number is actually low as nuclear weapons are under the Department of Energy and thus not generally calculated as part of the $700 billion budget). It is difficult for students and professional alike in American culture to not absorb the ethos of making weapons or intrinsically thinking of how to automate away jobs. This is part and parcel of the Silicone Valley ethos of disruption, as a value in of itself (see Google and Facebook’s enthusiastic mangling of journalism’s business models without regard to what that would do to civilization).

As the rising waters from Moravec’s illustration drown more and more white collar jobs, the traditional refrain that technological progress liberates people to do more meaningful work loses validity (the 1945 NYC Elevator Operator’s Strike is a useful prism for this).

Also, the fact that the majority of Americans have less than $1000 in savings means disruption for its own sake is something society cannot afford.

Yet, the future is coming with a tidal gravity so what are we to do?

One tool I’ve developed is the use of storytelling to create prototype technology with fascinating ancillary applications.

After witnessing conflict in DR Congo as a journalist, I wanted to use storytelling (filmmaking in this case) to inspire people to work to make the world a more wonderful place in particular by focusing on the solvable plague of landmines.

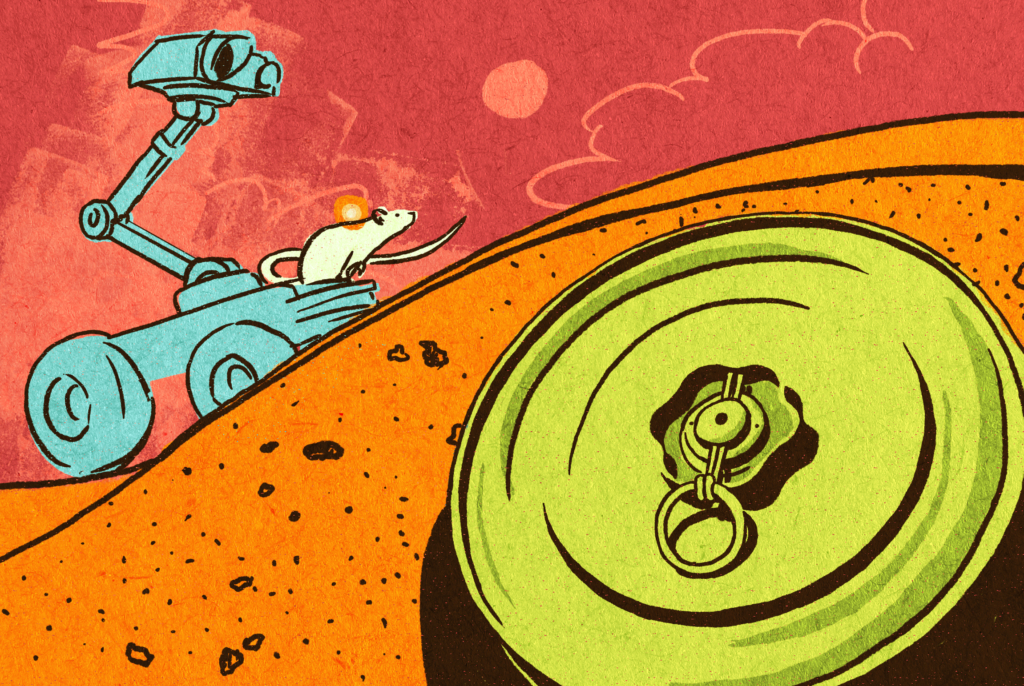

What I did was to write and direct a love story between a rat and a robot who guide humans who have gone mad stranded in a minefield to safety. My story has one extraordinary component that is real (a rat! Rats are actually trained to find landmines and detect tuberculosis by an organization called APOPO) and one out of fantasy (the robot companion).

However, in the process of making the movie I became entranced and fascinated with the idea of making the robot in reality. After all, aren’t robots just enchanted puppets? If Geppeto could do it, why not me?

I first started by going to famous puppet makers (Los Angeles can be a magical place) with the instructions to “create the most adorable machine in the world”. I had an idea at the time that it would be profoundly difficult to make a ‘Hello Kitty’ killer drone.

Then, with the visual reference a small team of humanitarian and technologists formed and with a maker’s spirit we went about trying to make the robot from the movie into a reality.

After much effort two key things were realized at this point.

1) A well-behaved rat that would gingerly take food from a human’s hand would violently attack a robot containing food so the entire robot/rat relationship was technologically unfeasible.

2) Computer vision is incredibly good at certain things but detecting rat feet scratching from a variety of angles is not one of those things.

A limit had been reached and I was close to moving on when I was invited to a lecture by an artist and roboticist who specializes in creating robots that commune with animals in nature. I cornered him afterwards and started to learn from him and after some more tinkering forward he had the idea of placing a sensor on the rat to detect the rats motion-signals and with this insight the technology could move forward (you may learn more about the details of all this from this TEDx speech I gave).

So, now the functionality of an external robot was being replaced by what’s essentially a very precise Fitbit that senses the animal’s motion and streams the data it out in real-time.

However, in order for this to be successful we need to be able to evaluate the data stream coming from the rat in real-time and only an artificial intelligence can do that and that is what we are developing today!

What began as a story about a rat and a robot has become an affordable wearable technology that uses artificial intelligence to facilitate communication between a rat and a human!

With further development hopefully this can be used in mine fields in service of saving lives.

However, If you stop and think you’ll come up with other applications for this technology and way of thinking in many other industries!

Ultimately, it was the act of having a story and then trying to make the story reality that made the preceding happen.

There’s a vastly useful and replicable methodology here to take us out of our professional and cultural modalities and that is precisely what we need to do to solve the onslaught of political, economic, and technological problems/opportunities that are here or emerging on the horizon.

What story would you tell that can take our reality to a new place?