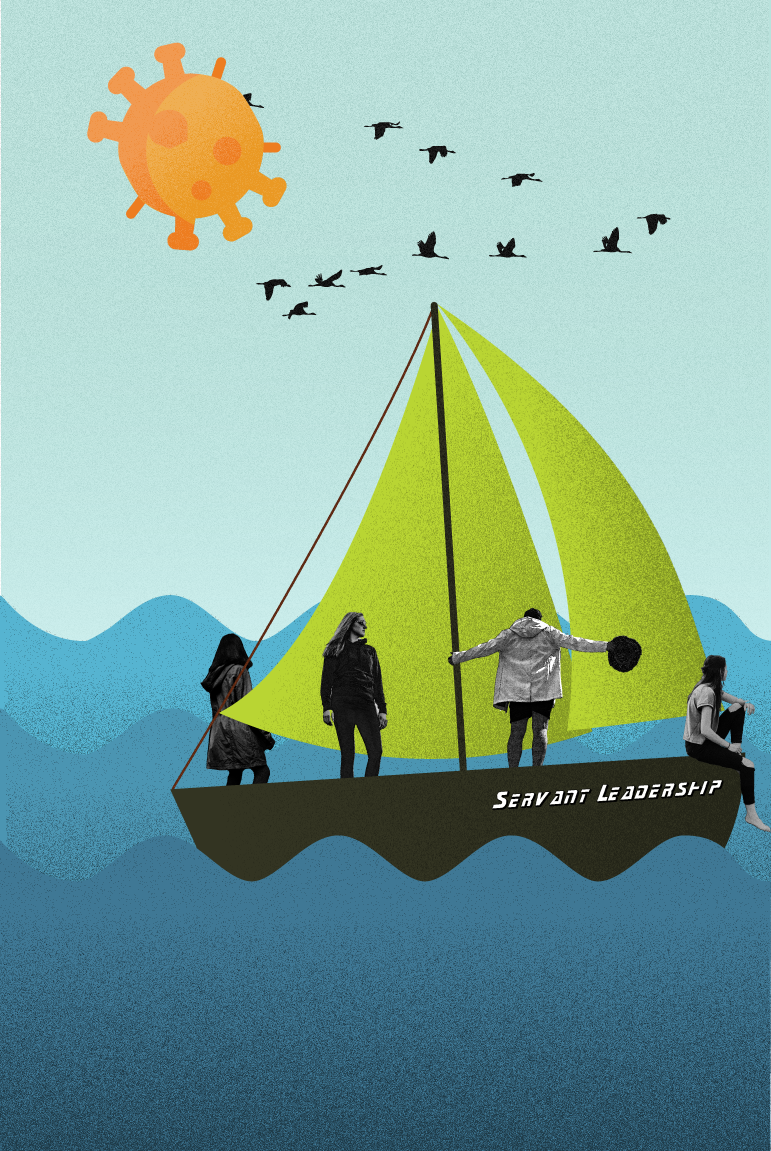

At Treeline we increasingly found that the processes we used for solving client problems needed some serious restructuring, and we had the good fortune to stumble upon the Design Sprint structure developed by author, design guru, former Googler, and super tall guy — Jake Knapp. We immediately became devotees and incorporated a great deal of his insights and thinking into our methodology. Jake is an expert in all things sprint having ran over a hundred sprints with well-known companies such as, 23andme, Blue Bottle and Slack. His book serves as a guide to answering those critical questions each business finds themselves asking. So when we decided to launch At Startup Speed, Jake was one of the first people we reached out to in order to pick his brain and share some amazing insights into the process he has become synonymous with. Your book Sprint — correct me if I am wrong — has been out for almost 2 years and you have been writing online about the topic for a while now. When was the a-ha moment that you said, hey this process may be working and worth sharing with others? Did you expect so many people and companies to be this interested in your process? When I was at your LA workshop the place was packed and people really were excited. What does the design sprint do best? One area of Sprints we have been experimenting with at Treeline is the best way to handle hardware. We’ve tried using decks, animations, non-working 3d printed designs, buggy POCs and pretty clean MVPs to give people the sense of the product. I can’t say honestly that anything works anywhere near as well as having a working MVP. I know it’s something you have given a lot of thought to. What have you seen work or not work when trying this process for hardware? We just did a sprint to develop out an accelerator program for a client and I can say it worked, but there was a lot of adaptation, some follow up work, and a lot of realization that we needed to structure the upfront differently as well. What won’t sprints work for? What type of corporate/startup business decisions should you avoid at all costs when utilizing this method? It’s much more of a marathon those first 2 days than a “Sprint”. How do you keep the energy and focus up when people start to slip? Besides the perfect high five exercise, can you share a great tip for being a better moderator and getting a roomful of people working together? As you may remember, I’m a bit of a complainer, and you might remember my comments on Slack about what I perceived as fussiness that seems to be emerging in an attempt to incrementally improve the sprint process — special sprint apps, recruiters for interview subjects, etc. How do best weigh the cost of incremental improvement over impact. What hacks to the Sprint process — such as the 4 day version — have really stood out to you? After well over 100 sprints, writing a book, anad your workshop tour, is there anything you wish you could add in the book or anything totally new that has occurred to you to make the process stronger? And if you found our chat with Jake interesting–and how could you not — be sure to check out his amazing book Sprint and don’t miss an episode of his awesome podcast. Illustration by Aneta Fontner-Dorożyńska

After writing the first blog posts in 2012 and 2013, when people started writing back and saying “We tried it, and it worked!” then I thought, a) that sucks, because I kinda hoped the sprint process worked just because I was such a great facilitator, but then I got over that and I thought, b) that’s cool, and, yeah, I want to keep on sharing this and help it spread.

No, I mean, when I created the process, I just wanted to change how we built products at Google, and I thought that was an almost impossibly big task. I’m thrilled that it’s been so useful to so many people, and I guess at this point I really believe in the process and I understand why it works so well—but in the beginning, I never expected such a thing to happen. It’s super cool.

It replaces the flawed workplace defaults with a system—and that system frees us up to do our best work.

Sprints can help answer a question about one slice of a hardware product. I’ve tried a lot of the things you mention, and I believe you can learn something—you can test the marketing and get some early sense for product market fit, you can test a 3d printed design and get some rough sense for ergonomics. In the end, the sprint is only a simulation, and when it comes to hardware, the finished product is always going to be a way different thing than a prototype. But I think it’s a mistake for people to say “because finished hardware is impossible to fake, we should spend months/years following a hunch.” It is especially helpful to improve your hunches when you’re building hardware, and a sprint can help you improve your hunches.

What you describe sounds like a success story to me—you’ve run several design sprints by the recipe already, so you knew what was a logical experimentation to do, and you did it, and some things worked but some didn’t, and if you did it again you’d do it even better. That’s a powerful skill I’ve seen teams unlock when they run sprints—they start to see the process as a thing that can be redesigned, experimented with, and they can improve it over time. As for projects where you shouldn’t do the classic design sprint? Don’t do a design sprint if the problem is too small. And if the problem is too big, where you don’t even have an idea yet for a business, be very wary of a design sprint. It is not going to magically create a business out of nothing. It’s a great way to start solving a big problem.

That’s when it’s so important to have a big problem—I think passion for solving the problem is key to getting the team through the start of the sprint. Design sprints are not the easy path—the easy path is probably to keep doing what you’re already doing. Of course, the easy path comes with lots of unnecessary pain and unnecessary work, but it happens slowly over a long period of time. Doing a sprint is hard work. And one thing that can help is if you remind the team “This is hard, but it will be worthwhile. I’m asking for your best effort because this project really matters. This is the reason we’re working on this team in the first place, and the reward for this hard work is we get to do thing we all care about.”

I can share 24! 🙂

The ones that stand out are the techniques that make the map and storyboarding easier, because those are really challenging parts of the process for a new facilitator, and they can be tiring even for someone with a lot of experience. The agency AJ&Smart have done some good work there.

Yeah, the bummer about books is you can’t just publish version 1.01. So I’d like to add in some of those tweaks people have come up with, and some tweaks I came up with after the book was already in production. But the good news is that none of those are super major changes. The recipe in the book is a darn good recipe and even if it isn’t 100% perfect, it’s robust and it works and people should feel confident using it.

Jake Knapp interviewApril 30, 2018