How a city capitalized on a growing start-up scene for innovative success

As Civic Innovation Specialist, you hold a pretty intriguing title. What does your role entail?

I manage PGH Lab, which is a city-wide program connecting local startups with the City of Pittsburgh. We connect with startups that need our help—whether it’s with gaining access to their first customer, or in learning how to do market research. For the most part, we target startups with a beta-stage product or service that they want to test. We deal in launching their pilot projects.

How long has this program been in place?

We started out as a pilot program in 2016 and we only accepted 3 startups at the time. The reason for that was we first wanted to see how the whole program would play out. The pilot went very well, so we decided to launch a second trial program, this time accepting 5 startups. We’ve just wrapped up our third cohort, which was the biggest of all three—we were working with 7 startups—which makes for a total of 15 over all three cycles.

The program itself has been growing exponentially, and the demand surrounding it has been growing along with it. We can see that through the number of submitted applications, and we also monitor it with our engagement tool. Our main goal is to provide access to local startups, and to engage with them in a way that proves helpful and provides value. In return, the city gets to experiment with new technology, right here at home.

What kinds of startups have made it through the program?

Last cycle, we had a company, Global Wordsmith, testing a language access consulting stack. They needed an organization where they could deploy this idea, which meant they were ready to go from day one.

In past cycles, we’ve had a composting company, Steel City Soils, that wanted to test how wood chips from the forestry division of the City of Pittsburgh would work with their method of composting. We had another company, Cropolis, working on an e-commerce software system for farmers’ markets. We happen to run the farmer’s market in the city, so they had access to that as well. We had another company, Meta Mesh Wireless Communities, that provided a mesh network to increase internet connectivity. NetBeez was a company that deployed sensors that can tell you from the user’s perspective whether the wifi and the network is working. They provide a dashboard where network engineers can see issues with the network.

What resources do you provide to each cohort?

Overall, a startup that goes through PGH Lab gets to learn how government works and is given the opportunity to engage with government at yet another level after the pilot. In a broad sense, we do everything we can to ensure that our program participants yield successful pilots and deliverables. We make sure they get connected to the resources they need, and we also try to make sure they get as much feedback on their product or service as possible.

Given what we do, it’s important to us to cultivate and maintain really good relationships with other organizations, accelerators, and incubators in Pittsburgh. As a result, we have direct access to many mentors and contacts in the entrepreneurial community. In addition, we offer education and resources—we hold classes on government procurement, which enables a better understanding of that process. We also help participants develop and utilize the tools needed to engage with vendors.

Our main goal is to provide access to local startups, and to engage with them in a way that proves helpful and provides value. In return, the city gets to experiment with new technology, right here at home.

How does a startup get to work with you? Can you give us a brief look into the application process?

Startups initially apply to be placed with any participating organization within the innovation platform—including the City of Pittsburgh, the Urban Redevelopment Authority, and the Housing Authority. All these authorities work independently, but function as local government institutions. By submitting just one application, startups become eligible to pilot their project alongside any of the participating organizations within the program.

We ask startups to propose a solution in four different categories: citizen engagement; city operations; climate change and environments; and other. If a startup has an idea that lies within the scope of suggested categories but doesn’t quite seem like it fits in any singular one, they file that in the “other” category and explain it to us in further detail in order to be considered. Once they’ve passed the second round of the selection process, the contending startups get invited to a pitch session. Finally, we make our selection and a cohort is born.

Startups that successfully make it through the selection process get access to coworking spaces, where they work for 3 to 4 months. They also get matched with city employees called “City Champions,” who act as mentors and facilitators of their pilot projects. At the end of each cohort’s project phase, we organize a community event where startups get to share their findings and what they learned from their proof of concept.

How do you decide on candidates?

We have a guiding set of criteria that we put forth in our applications. We’re definitely looking for early-stage startups with a working prototype. Or, if they are a service, they need to have a clear idea of what it is they’re trying to achieve. That aspect is key, because the startups are expected to test their solution when we start the pilot. Usually, we get young companies that are between one and five years old.

We also aim to have an open approach in terms of solutions, which provides us with a variety of creative and innovative projects in each cohort. As a result, we’ve had a diverse range of pilot projects that have come out of our three cycles. On the cohort-level, it paves the way for some great connections, and it ensures that we have a little bit of everything in each cycle that we do.

Who decides which startups get accepted into the program?

Our selection process is carried out by a centralized review committee right here in the city, mostly made up of department directors and representatives from different authorities. Each representative has their own area of expertise, and they’re also more aware of the particular solutions involved in developing these projects. They’re the ones who vet all the applications and solutions for a particular cohort. They’re also the ones who volunteer and connect with the City Champions, who go on to co-create and co-run the pilot projects. The committee itself plays a key role in recruiting City Champions, vetting the applications and choosing the best solutions.

The program has been really well-received by the community. Do any members of the cohorts go on to have paid partnerships with the city?

Although we do not provide a path to procurement, we have had companies that have gone on to paid engagements. In the second cohort, we had a company named Flywheel that was working with the Urban Redevelopment Authority. They worked so well with their City Champion, who decided that three months would not be enough for the things that he wanted to improve in his area and the things he wanted to test, so they transitioned to an extended and paid engagement with him. There may be more opportunities like that, but we’re not sure yet what they’ll be or when they come up.

Do you ever find any difficulties working with the City?

There are always challenges because of the way government works and the varying ways that startups work. This program allows startups to experience a little bit of both. The way the program is set up, pilots are set for a limited amount of time, and startups have to meet their milestones and deliverables. So, I think there are always challenges in regards to timing.

The main driver of success is finding the right City Champions that will really endorse each pilot project, and guide and facilitate access to whatever the startup needs to get to make their project successful.

So far, we have had great City Champions who are motivated and care about improving the projects they’re matched to work on. We have been lucky that they have been big advocates for startups and their projects. The City Champions are integral to making the program work—without them, we really cannot engage all the startups we’d want. We rely on City Champions to provide access and as much feedback as possible—this is a critical aspect of the program and arguably the most important part of a successful project launch.

Would you say the community has embraced what you’re doing?

The entrepreneurial community in Pittsburgh is very collaborative. People care about the startups and the entrepreneurs, and they go the extra mile to inform everyone about available resources. The accelerators and incubators like Alpha Lab Gear, Innovation Work, and Idea Foundry, are a big part of the pipeline in recruiting new startups. We also try to engage with as many people as we can through community events. Finding those points of connection and making sure that the startups get to know what kind of resources are in the city is very important to us.

The main driver of success is finding the right City Champions that will really endorse each pilot project, and guide and facilitate access to whatever the startup needs to get to make their project successful.

This is a fairly unique program; there are maybe only 5 or 6 others like it in the country. What makes Pittsburgh so successful?

We’re learning and adjusting as we go—we try to learn and gain as much data as possible in order to improve with each cycle. We try to implement all of the feedback that our startups and community partners give us as quickly as possible. This has allowed the program to expand in scope and scale. I think that making decisions quickly and learning from these experiences has been key.

Some time ago, I connected with the City of Durham in North Carolina. They were preparing to launch a program like PGH Lab earlier this year, and they wanted to learn the ins and outs before they dove in. They just launched their first cohort, and I’m really looking forward to connecting again and seeing what they’ve learned and what their experiences were.

I think keeping a close eye on the program, making sure that we are very supportive of the startups, and learning from any mistakes and data has been key to our success.

What do you think makes your program attractive when competing with other cities like San Francisco, Boston, or LA? What makes Pittsburgh so unique?

We have had companies that have not had the opportunities to test products and services at a larger scale. In our first cohort, we had a company called HiberSense, and they do microclimate control sensors and reporting. Before PGH Lab, they thought they would only be useful in residential areas. They applied to PGH Lab to see how the sensors and the whole solution would play out in an office environment. After the pilot, they decided their solution was not only targeted to residential areas, but also would do well with office spaces. As far as I know, now they’ve connected with a number of different managers, and the University of Pittsburgh is using their solution in their buildings and offices.

For a young startup looking how to scale or looking for different ways in which their product can affect users, PGH Lab really opens that opportunity for them.

Do you have partnerships with the local universities?

We do—they help us raise awareness about the program and provide access to the application. I’ve had informational sessions with other universities, and that also proves really important. As far as I remember, each cohort has had a university startup. Last cohort, we had a spin-off from Carnegie-Mellon University’s project, Olympus Incubator, that was placed with the Parking Authority.

Do you have a success story that you’re particularly proud of?

I think each of the startups presents a unique solution. Overall, we are very proud of our cohorts. HiberSense had a really strong pilot and went to seek for funding at the Urban Redevelopment Authority. In 2017, HiberSense participated in a local big idea competition called UpPrize – Innovation Social Challenge where they won $60,000 to keep improving their products and business model. They have been a great local success story.

What goes on behind the scenes to transform a city into an innovation hub?

I think places like PGH Lab represent the meeting point between the two worlds that work towards creating change within a city. On the one hand, the support from people in leadership roles mobilizes people within the city; on the other hand, the resources and networks provided by pre-existing systems like local incubators and accelerators help us get the word out to startups we might not otherwise come into contact with.

HiberSense was launched out of the University of Pittsburgh, correct?

That’s correct. The University of Pittsburgh has an accelerator called Blast Furnace and I think they came out of that accelerator and got some funding. Then, they got into Alpha Lab Gear, which is one of the local accelerators, and then they applied to PGH Lab to test their beta-stage sensors. The company has been seeking funding from the Urban Redevelopment Authority as they fund early tech startups with great potential to grow.

I think places like PGH Lab represent the meeting point between the two worlds that work towards creating change within a city.

You have all become leaders and experts in the field of startup incubation. Have you pivoted your model at all over the past three cycles?

Not entirely, but we’re always exploring ways to improve the model—especially for the upcoming cycle this fall. Right now, we’re in the planning phase and we’re considering how we can improve from our last cohort. Our City Champions are really excited to be participating in the next cycle, and we’re hoping to recruit more people to get involved with PGH Lab.

What is the future for PGH Lab, or other municipal accelerators in general?

Of course, we would love to keep on growing—and we want to invite more testing partners to work with us and to act as platforms for innovation. For the first cycle, we started with the Urban Redevelopment and the City of Pittsburgh as our partners. In the second cycle, we added in the Housing Authority, the Parking Authority, and the Pittsburgh Water and Sewage Authority. We’re always looking to recruit testing platforms so that we can engage more startups. We’re also open to sharing our lessons learned and best practices so other cities can also implement something similar. It’s one very direct way to help local entrepreneurs. And if we did it, others cities can do it.

Is there one guiding philosophy or mantra at the core of what PGH Lab represents?

If I were to sum it up in three words, I’d say: quality, collaboration, and partnership. A program like PGH Lab not only engages a particular community, it invites all of its members to suggest and co-create solutions that improve the city’s infrastructure, the life of its residents, and the greater community as a whole. We want to show that we are listening to the community and that we are working together to address the complex challenges commonly faced in urban areas today. And we want to continuously improve the services that we and the City provide, especially through building strong partnerships and leveraging opportunities for collaboration.

Annia Aleman is the manager of PGH labs, which connects the City of Pittsburgh and local authorities with local startup companies to test new products and services. Annia has experience in civic innovation, public-private partnerships, government, program management & design, data analysis, and report writing while working world wide. She is also fluent in both Spanish and English.

Updates: PGH labels is accepting applications for PGH Lab 4.0, application deadlines are September 28, 2018. They also welcomed a new testing partner for this cycle, the Allegheny Conference on Community Development. A non-profit that helps drive improvement of the economy and quality of life in our Pittsburgh region. One of their startups in the third cohort did get a paid engagement after PGH Lab 3.0 so that makes two companies have had paid engagement after their pilot project. The company is called NetBeez.

Follow Annina on LinkedIn and Twitter

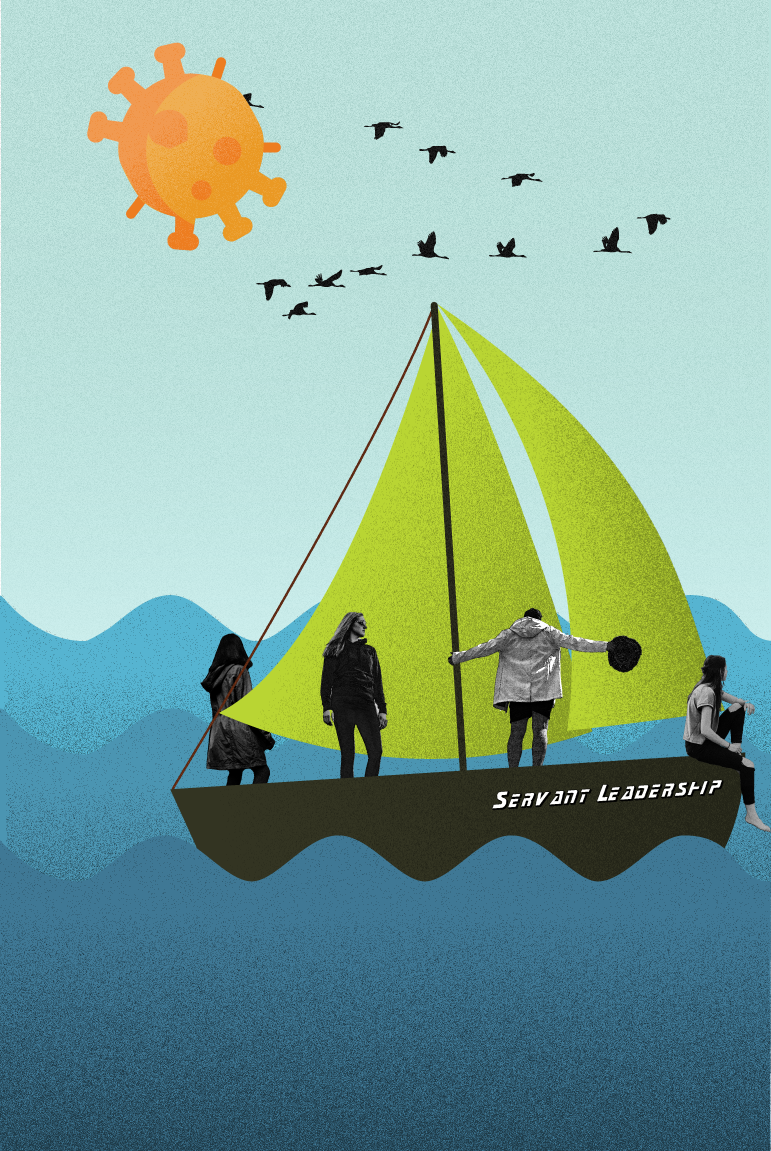

Illustration by Katarzyna Księżopolska